![]() Podcast: Guido Schwerdt talks with Ed Next about his new study.

Podcast: Guido Schwerdt talks with Ed Next about his new study.

An unabridged type of this information is available here.

In the past svereal years, a consensus has emerged among researchers that teacher quality matters enormously for student performance. Students taught by more-effective teachers learn substantially more over the course of 12 months than students taught by less-effective teachers. Yet little is known in regards to what is a more-effective teacher.

In the past svereal years, a consensus has emerged among researchers that teacher quality matters enormously for student performance. Students taught by more-effective teachers learn substantially more over the course of 12 months than students taught by less-effective teachers. Yet little is known in regards to what is a more-effective teacher.

Most research on teacher effectiveness has dedicated to teacher attributes, discovering that readily measurable characteristics just like experience, certification, and graduate degrees generally little affect on student achievement. Relatively few rigorous studies look into the classroom to observe in the marketplace teaching styles are classified as the most efficient. We tackle this underexplored area by investigating the relative link between two teacher practices-lecture-style presentations and in-class problem solving-on the achievement of middle-school students in science and math.

Ever since John Dewey explored hands-on learning with the University of Chicago Laboratory School more than a century ago, lecture-style presentations have been criticized as old-fashioned and ineffective. You are able to, as an example, that lectures presume that most students learn on the same pace and cannot provide instructors with feedback about which elements of a lesson students have mastered. Students’ attention may wander during lectures, and they may without difficulty forget information they encountered within this passive manner. Lectures also emphasize learning by listening, that might disadvantage students who favor other learning styles.

Alternative instructional practices depending on active and problem-oriented learning presumably really don’t are afflicted with these disadvantages. But they might have their own individual shortcomings. Learning by problem-solving could be less capable, as discovery and problem-solving often much more than mastering information received from a specialist figure. And incorrect or misleading information could be conveyed in conversations among students in middle schools.

Nonetheless, various small-scale research has identified positive impacts of interactive teaching styles on student learning. Therefore, prominent organizations like the National Research Council as well as National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, since as a minimum 1980, have called for teachers to have interaction students in constructing their particular new knowledge through more hands-on learning and group work. From the mid-1990s, inside of a study for the National Institute for Science Education, Iris Weiss could identify “some encouraging signs. Virtually all elementary, middle, as well as school science and mathematics classes worked in small groups one or more times 7 days, and roughly a quarter of classes did so each day. Moreover, the effective use of hands-on activities had increased since mid-1980s.” Even so, higher than a decade later, traditional lecture and textbook methodologies continue to be a significant component of science and mathematics instruction in U.S. middle schools. A radical, large-scale study has yet to settle a concern which includes divided pedagogical thinking for generations.

In our study, we examine whether student achievement in the United States is plagued by the proportion teaching time devoted to lecture-style presentations as distinct from problem-solving activities. Employing information on in-class time use given by a nationally representative sample of U.S. teachers while in the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), we estimate the outcome of teaching practices on student achievement by checking differential effects on the very same student of two different teachers, using two different teaching strategies. We find that teaching style matters for student achievement, employing the opposite direction than anticipated by the usual understanding: a focus on lecture-style presentations (as opposed to problem-solving activities) is part of an increase-not a decrease-in student achievement. This result means that a shift to problem-solving instruction is far more planning to adversely affect student learning rather improve it.

Data and Methodology

Our research draws on data with the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). The TIMSS data comprise specifics of students in just two grades in many different countries, but we utilize only specifics of 8th-grade students in the United States. Our sample includes 6,310 students in 205 schools with 639 teachers (303 math teachers and 355 science teachers, of which 19 teach both subjects). As well as test scores in math and science, the TIMSS data include pay-to-click sites students’ home and family life and also data on teacher characteristics, qualifications, and classroom practices. School principals carry school characteristics.

Most vital for our purpose, teachers were asked what proportion of energy inside a typical week students invested in each of eight in-class activities. The complete amount of time in class apportioned to three of the activities-listening to lecture-style presentation, perfecting difficulties with the teacher’s guidance, and on problems without guidance-likely gives a good proxy for the time in class where students are taught new material. We divided the time spent hearing lecture-style presentations through the total amount of the time allocated to these three activities to develop a single way of measuring the span of time the teacher about lecturing compared to the time was devoted to problem-solving activities.

A alter in our way of measuring teaching style could be interpreted as a shift from hanging out on one practice to hanging out on the other, holding constant the full time devoted to both practices. One example is, an expansion of 0.1 shows that 10 percentage points of total time devoted to teaching new material are shifted from teaching determined by solving problems to giving lecture-style presentations. We combined the opposite teaching activities (besides lecturing and solving problems) right into a separate way of the share of total teaching time devoted to other pursuits and control due to this measure throughout our analysis. Furthermore control for the count of minutes in a week that the teacher reported teaching the math or science class, for the people seeking total instructional time would have an unbiased relation to student learning.

Although it is difficult to know on the TIMSS data precisely how much time is used lecturing as distinct from problem-solving activities, apparently teachers generally observe the advice written by progressive educators. Normally, they allocate double the time and energy to problem-solving activities in respect of direct instruction. Specifically, teachers devote about 40 % of sophistication time for it to problem-solving activities (with or without teacher guidance); during roughly 20 % of class time, students take notice of the initial presentation of cloth to become learned. The rest of the class time is assigned to such tasks as class management, reviewing homework, re-teaching the fabric, and clarifying content (see Figure 1).

Although it is difficult to know on the TIMSS data precisely how much time is used lecturing as distinct from problem-solving activities, apparently teachers generally observe the advice written by progressive educators. Normally, they allocate double the time and energy to problem-solving activities in respect of direct instruction. Specifically, teachers devote about 40 % of sophistication time for it to problem-solving activities (with or without teacher guidance); during roughly 20 % of class time, students take notice of the initial presentation of cloth to become learned. The rest of the class time is assigned to such tasks as class management, reviewing homework, re-teaching the fabric, and clarifying content (see Figure 1).

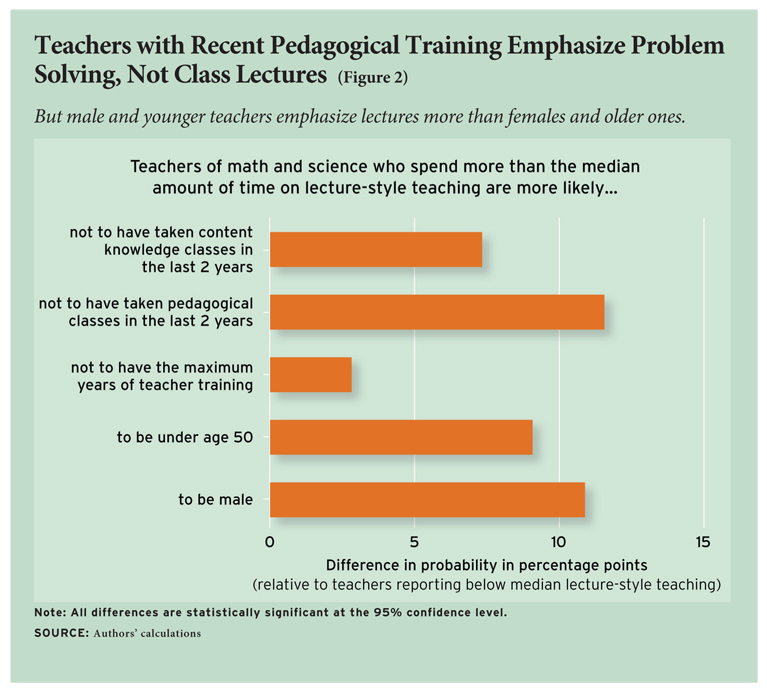

Teachers who spent more time lecturing were very likely to be male and under age 50. Interestingly, they had been also unlikely to have maximum number of many years of teacher training registered via the background survey or to have got pedagogical or content knowledge classes within the prior two years (see Figure 2).

A key challenge in staring at the effects of teaching practices is usually that teachers may adjust their methods in response to your ability or behavior within their students. If teachers tend to rely on lectures when assigned more capable or attentive students, this might come up with a positive relationship between your time frame spent lecturing and student achievement, even in the absence of an actual causal effect. Similarly, there can be unobserved differences between students whose teachers rely many less heavily on lecturing if, for instance, teachers in schools serving low-income students adopt different practices than teachers in some other type of schools.

A key challenge in staring at the effects of teaching practices is usually that teachers may adjust their methods in response to your ability or behavior within their students. If teachers tend to rely on lectures when assigned more capable or attentive students, this might come up with a positive relationship between your time frame spent lecturing and student achievement, even in the absence of an actual causal effect. Similarly, there can be unobserved differences between students whose teachers rely many less heavily on lecturing if, for instance, teachers in schools serving low-income students adopt different practices than teachers in some other type of schools.

To address these concerns, we exploit the truth that the TIMSS study tested each student both in mathematics and science. This will give us to compare the mathematics and science test countless individual students whose teacher in just one subject tended to emphasise an alternative teaching style than their teacher in the other subject. This means that, we ask, if the given student’s math teacher spent more (or less) time lecturing than his or her science teacher, does the student perform better or worse around the math test than you are on the science test?

Results

Contrary to contemporary pedagogical thinking, look for that students score higher on standardized tests in the subject whereby their teachers spent more time on lecture-style presentations compared to this issue that teacher devoted more of their time to problem-solving activities. Equally for math and science, a shift of 10 percentage points of energy from problem-solving to lecture-style presentations (e.g., improving the share of your time spent lecturing from 20 or 30 percent) is owned by more student test countless 1 percent on the standard deviation. An alternate way to state the same finding is always that students learn less within the classes during which their teachers take more time on in-class solving problems.

Importantly, the effectiveness of the partnership increases when you restrict our analysis to the roughly one-third of students while in the TIMSS sample who had this also peers within their math and science classes. Among this gang of students, a shift of 10 percentage points of your time from problem-solving to lecturing is part of a rise in test a lot of almost 4 % of the standard deviation-or between 1 and 2 months’ in learning inside of a typical school year (see Figure 3). This pattern increases our confidence that the overall result will not reflect differences in the peer composition of students’ math or science classes. The fact is, it shows that peer effects may actually be leading us to understate the effectiveness of the marriage between lecturing and student learning.

Importantly, the effectiveness of the partnership increases when you restrict our analysis to the roughly one-third of students while in the TIMSS sample who had this also peers within their math and science classes. Among this gang of students, a shift of 10 percentage points of your time from problem-solving to lecturing is part of a rise in test a lot of almost 4 % of the standard deviation-or between 1 and 2 months’ in learning inside of a typical school year (see Figure 3). This pattern increases our confidence that the overall result will not reflect differences in the peer composition of students’ math or science classes. The fact is, it shows that peer effects may actually be leading us to understate the effectiveness of the marriage between lecturing and student learning.

Do certain kinds of students benefit more from lectures than other people? We look for suggestive evidence that this relationship between lecture-style teaching and achievement is strongest among higher-achieving and more-advantaged students. One example is, the positive effect is largest for kids who report having many bookcase in your house, an uncertain indicator from the quality within their home environment. There isn’t a evidence, however, that lower-achieving students or students from less-advantaged backgrounds learn less when their teachers emphasize lectures.

These patterns are similar to the findings of any 1997 study by Dominic Brewer and Dan Goldhaber, which discovered that more in-class problem solving for American 10th-grade students in math relates to lower test scores with a standardized test. Because our email address details are determined by comparisons from the student by two different classes, however, they are less governed by the concern that teachers adjust their practices based on the students where they can be assigned. Furthermore, the other commonly investigated teacher characteristics (e.g., gender, experience, and credentials) do not show significant effects on student achievement within our analysis. This is often in keeping with previous findings inside the literature and underscores the importance of the statistical relationship between more lecture-style teaching and student achievement.

While the richness with the TIMSS data enables us to master for any unusually large range of teacher characteristics, our results could certainly biased if teachers with some other effectiveness levels tend to choose different teaching styles. One example is, if more-effective teachers tend to take more time lecturing considering they are good at it and get it, then our results could show a positive effect of lecture-style presentations, even though those teachers would have been all the more effective had they devoted longer on problem-solving activities. As a result of pedagogical emphasis on the application of problem-solving activities, it appears to be unlikely that the absolute best teachers might be using the less-effective teaching style (the one alternative reason behind our finding).

Still, it is very important take into account that our email address particulars are restricted to student achievement as measured with the 2003 TIMSS test scores in 8th-grade math and science in the states. Different results can be found for many different subjects, grades, or tests. With regards to the teacher, students, the material taught, or other factors, problem-solving activities could turn out to be the more suitable style. Even though lecture-style teaching definitely seems to be a far more effective method in middle-school science and math, which doesn’t mean it is the preferable method of elementary-school reading.

Also, our findings use student performance for the TIMSS math and science exams, which have been designed to measure mastery of factual information about the curricula that schools expect students to find out. Other tests developed to measure problem-solving ability as well as competence to utilize mathematical and scientific concepts in real-world settings (such as Programme for International Student Assessment [PISA] administered by the Organization of monetary Cooperation and Development) might yield different results. Unfortunately, we’re also can not ascertain whether this might be true, as PISA did not ask teachers regarding pedagogical approach.

Finally, our home elevators teaching practices, that is based on in-class time use reported by teachers, will not permit us to separate different implementations training practices. Quite simply, a certain teaching technique can be quite effective if implemented from the optimal way. Although the strength individuals approach is that it examines which teaching style is effective, generally, for teachers normally. Optimal teaching techniques that is not executed by teachers on the whole may do more harm than good.

Conclusion

Given suffers from limitations on the data, our finding that spending increased time on lecture-style teaching improves student test scores results really should not translated towards a require more lecture-style teaching usually. Nevertheless the results do claim that traditional lecture-style teaching in U.S. middle schools is less of a problem than can often be believed.

Newer teaching methods could possibly be necessary for student achievement if implemented from the correct way, but our findings signify simply inducing teachers to shift amount of class from lecture-style presentations to problem-solving without ensuring effective implementation isn’t likely to improve overall student achievement in math and science. Not so, our results indicate there can even be a harmful affect on student learning.

Guido Schwerdt is often a postdoctoral fellow at the Program on Education Policy and Governance (PEPG) at Harvard University including a researcher at the Ifo Institute for Economic Research in Munich, Germany. Amelie C. Wuppermann is usually a postdoctoral researcher along at the University of Mainz, Germany.

An unabridged sort of pros and cons available here.